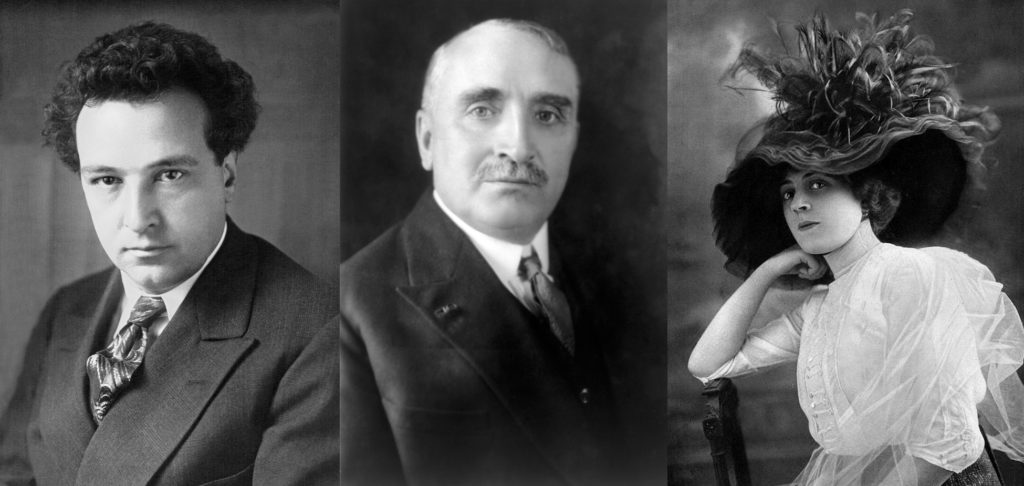

Ida Lvovna Rubinstein was a Russian dancer, actress, art patron, and Belle Époque figure, born in 1883 to one of Russia’s richest families. By the time she was nine years of age, both of Ida’s parents had died, leaving her with a large fortune. In 1893, orphan Ida was sent to Saint Petersburg to live with her aunt, the socialite “Madame” Gorvits. Rubinstein grew up in her aunt’s mansion on the city’s famed Promenade des Anglais, where she was given the best education, eventually becoming fluent in four languages, and instructed in music, dance, and theatre. She lacked natural dance ability, and by the high standard of Russian ballet, little formal training. Eventually, secretly intent on going on stage herself, she went to Paris to continuing her education. Using her inheritance and love of the arts and performing, Rubinstein decided to form her own dance company, and commissioned several lavish productions, continuing to perform and stage free ballet events until the start of the Second World War.

Born Oscar-Arthur Honegger on March 10, 1892, in Le Havre, France, to Swiss parents, Arthur Honegger became a student of Charles-Marie Widor and Vincent d’Indy at the Paris Conservatoire. In 1926 he and fellow student Andrée Vaurabourg, a pianist, married with the condition they live separately. They had one daughter, Pascale, while Honegger also had a son, Jean-Claude, with French mezzo-soprano Claire Croiza. Honegger composed prolifically between World Wars I and II, but the outbreak of World War II combined with Nazi invasion, left him trapped in Paris. Though he joined the French Resistance, he was generally unaffected by the Nazis, who permitted him to continue his compositional work with minimal interference. Despite the expressive outlet of music, war greatly depressed him. Socially and professionally he was a member of Les Six, formalized in 1920, of which the forerunner, Les nouveaux jenues, was formed in 1917 by Erik Satie. Collectively, the music of Les Six is often perceived as a reaction to the compositional styles of Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel, and Richard Wagner, while individually the principal elements of Honegger’s style embrace Bachian counterpoint, driving rhythms, melodic amplitude, coloristic harmonies, an impressionistic use of orchestral sonorities, and a concern for formal architecture, and, in his later works, the influence of German romanticism.

Poet and playwright Paul Claudel was born into a family of farmers and government officials August 6, 1868, in Villeneuve-sur-Fère, France. While his formative years were spent in Champagne, a family move to Paris in 1881 put him on the path to enroll at the Paris Institute of Political Studies. As a teenager, he considered himself an unbeliever, but at the age of eighteen he experienced a sudden conversion on Christmas Day, 1886, while listening to a choir sing Vespers in the cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris. “In an instant, my heart was touched, and I believed,” he wrote. He remained a resolute Catholic the rest of his life. As a young man, Claudel seriously considered entering a Benedictine monastery, but in the end chose a career in the French diplomatic corps, in which he served from 1893 to 1936. His work took him to China, Bohemia (present-day Czechoslovakia), Germany, Brazil, Denmark, Japan, and Belgium. In April 1893, he served as the first vice-consul in New York, and later that year in Boston. Claudel’s artistic influences include the Symbolists and, in particular, Arthur Rimbaud. Similar to these writers, he was disgusted by contemporary, materialist views of life. His response was founded upon his religious beliefs. A unifying theme found in his writings is rejection of the concept of a mechanical or randomized universe. Rather, human life is founded upon a deep spiritual purpose premised upon the all-governing grace and love of God. Eight times Claudel was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature, though he never received the award.

It was Rubinstein who eventually brought Honegger and Claudel together. Rubenstein had commissioned a new work for her dance company from Honegger and, originally, she had selected Jeanne d’Orliac to write the libretto for the production. However, Honegger and d’Orliac did not get along. Rubinstein suggested Claudel, who was writing for her on another project. Honegger and Claudel met in November, 1934. Claudel was not inspired by the premise of Honegger’s project until he experienced a vision of a sign of the cross made by two linked hands, which stimulated him and he completed the libretto in about two weeks’ time. The work premiered in Basel, Switzerland, May 12, 1938, with Rubinstein in the role of Joan of Arc. The two also collaborated on 1938’s La danse des morts (The Dance of the Dead). The pair’s friendship continued and Claudel later wrote to Honegger in a 1942 letter, “Dear Arthur Honegger, this call to freedom and fulfillment, this auscultation around you of a world summoned to orchestral plenitude, is the domain where you gambol in full possession of your genius, where I have been given the opportunity to follow you, and sometimes even, I am proud to say, to lead you.”